Powder co-editors, together with contributing poet Rachel Vigil, are interviewed in a podcast released today by the Wandering Scholars program at University of Maryland University College Asia. Joining us was UMUC military science professor Aleta Geib, who has included Powder on the syllabus for her Spring 2009 course on women in the military at UMUC's Guam campus.

Listen here.

Monday, December 8, 2008

Monday, December 1, 2008

New Century, New War, and New Role for Women in the Military

Anna Osinska Krawczuk is the author of the Powder poem "War Terrorism." She is the Immediate Past National Commander of Ukrainian American Veterans. She was born in Warsaw, Poland, to Ukrainian parents. Krawczuk joined the Women’s Army Corps in 1955 in Newark, New Jersey, at 18 years old, just after becoming an American citizen. Part of her job was to run the film projector for officer briefings, some of which detailed the aftermath of liberated concentration camps. She was honorably discharged at age 21 and now draws from her time in the army for her poetry.

Anna Osinska Krawczuk is the author of the Powder poem "War Terrorism." She is the Immediate Past National Commander of Ukrainian American Veterans. She was born in Warsaw, Poland, to Ukrainian parents. Krawczuk joined the Women’s Army Corps in 1955 in Newark, New Jersey, at 18 years old, just after becoming an American citizen. Part of her job was to run the film projector for officer briefings, some of which detailed the aftermath of liberated concentration camps. She was honorably discharged at age 21 and now draws from her time in the army for her poetry.The history of women in America’s military service was often marked by gender discrimination, something felt even now in the fully integrated “co-ed” US Armed Forces. During the Civil War both the Union and Confederate armies forbade the enlistment of women. Women soldiers had to assume masculine names, disguise themselves as men. Some were killed in action, others were wounded. If a woman in the ranks was discovered, she were quickly dismissed from the military. Discharge documents dated April 20, 1862 for “John Williams” indicate the reason for mustering out was “that he was found to be a woman.” The most documented cases of that era are about Sarah Edmonds, alias Franklin Thompson, and a woman who called herself Albert D J Cashier – they served as registered nurse, mail and dispatch carriers. Sarah even received a government pension in 1886. Despite recorded evidence to the contrary, the US Army tried to deny that women played a role in the Civil War. Today, women serving in the military are socially accepted, thanks in part to the vision and courage of their predecessors, the women combatants of 1861–1865.

Until 1970 the highest rank for servicewoman was that of Colonel. Today, servicewomen hold higher ranks, and on July 23, 2008, the U.S. Senate confirmed the promotion of Lt Gen Ann E. Dunwoody to four-star general. She is the first woman to serve in the United States military as commanding general, US Army Materiel Command at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. Presently, over 200,000 women serve on land, at sea, in the air, and on space missions – including our own - American Astronaut, US Navy Captain Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper, crew member of the 27th Mission of Atlantis.

In 2006, US Air Force Thunderbird team included Major Nicole Malachowski of US Air Force, the first female demonstration pilot. Coast Guard Lt Holly Harrison was the first woman in the US Coast Guard to be awarded the Bronze Star while serving as commander of the Coast Guard Cutter Aquidneck in the waters near Iraq.

At this time, American women serving in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries are active participants in assigned missions and earn medals for courage. In Iraq, Sgt Leigh Ann Hester (of 617th Military Police Company) was the first woman soldier to receive the Silver Star since World War II. Spec. Monica Brown (82nd Airborne Division) received hers in Afghanistan. Chief Warrant Officer Lori Hill was awarded Distinguished Flying Cross for valiant flying under fire. And the list goes on and on.

We also have histories of Ukrainian-American servicewomen from World War II to Operation Iraqi Freedom. During WWII, Captain Tillie Kuzma Decyk served in US Army Nurses Corps and was awarded the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, WW II medal, and a Bronze Star to EAME Theater Ribbon. UAV members Mary Smolley Scott (Post 19) and Dorothy Sudomir Budacki (Post 28) both served in the US Navy; Mary Capcara Holuszczak and Irene Zdan (Post 101) also served. Flight nurse Evelyn Kowalchuk served in US Army Air Corps and was honored by President George W. Bush on D-Day Memorial dedication in Bedford, VA in 2001. We also know of Lt Olga Konopsky Pryjmak, who served in Viet Nam as a nurse. A WWII orphan adopted by American family, she met her husband Steven Pryjmak (himself a Purple Heart recipient) in Viet Nam (former UAV Post 30). Oksana Xenos of Post 101 served during the post Viet Nam era and attained the rank of Lt Col US Army, retiring in 1995. Maria Matlak – Lt Col US Marine Corps, retired in 1999. She was the 57th woman on active duty to attain that rank in 1982. This is just a short list—we know of many other women who have served and there are many whose histories are unknown to us.

I appeal to every servicewoman and/or veteran to register so that your story can be known and told. Register with Women in Military Service for America.

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Breaking into the Big Box

Shannon Cain is the co-editor of Powder.

As a nonprofit independent publisher, Kore Press believes fervently in supporting locally owned booksellers such as Antigone Books.

But ho, what's this? An invitation to sign books at Borders here in Tucson?

Last year, Powder co-editors joined literary activists Action Down There to promote an anti-consumerist, anti-war message. See photo of us carrying bags designed by Lisa Bowden, containing beribboned peace messages we handed out to unsuspecting shoppers. This in the very same mall we'll be visiting on Saturday for a booksigning.

We are learning to live with the irony. I'm not going to kid you...when our local Borders called us on Veterans Day and asked to place an order, we hustled the books right down there without a moment's hesitation. Suddenly we could imagine Powder on mall shelves nationwide.

But oh, how disconcerting to be signing books in the belly of the beast. Least we can do is plug the Arizona Local First campaign, which kicks off tomorrow with Buy Local Day.

But oh, how disconcerting to be signing books in the belly of the beast. Least we can do is plug the Arizona Local First campaign, which kicks off tomorrow with Buy Local Day.

Images from the Powder launch in Tucson

Veteran's Day 2008

Charlotte Brock reads from her essay "Hymn"

Charlotte Brock reads from her essay "Hymn"

Elizabeth McDonald reads her poem "Yes, Sir."

Elizabeth McDonald reads her poem "Yes, Sir."

Tucson poet Niki Herd reads Rachel Vigil's poem "Gear Up"

Tucson poet Niki Herd reads Rachel Vigil's poem "Gear Up"

Tucson poet Alison Hawthorne Deming reads Sharon Allen's essay "Lost in Translation"

Tucson poet Alison Hawthorne Deming reads Sharon Allen's essay "Lost in Translation"

Tucson City Councilmembers Nina Trasoff (left) and Regina Romero

Tucson City Councilmembers Nina Trasoff (left) and Regina Romero

U.S. Congressmember Raúl Grijalva makes opening remarks

U.S. Congressmember Raúl Grijalva makes opening remarks

Charlotte Brock reads from her essay "Hymn"

Charlotte Brock reads from her essay "Hymn" Elizabeth McDonald reads her poem "Yes, Sir."

Elizabeth McDonald reads her poem "Yes, Sir." Tucson poet Niki Herd reads Rachel Vigil's poem "Gear Up"

Tucson poet Niki Herd reads Rachel Vigil's poem "Gear Up" Tucson poet Alison Hawthorne Deming reads Sharon Allen's essay "Lost in Translation"

Tucson poet Alison Hawthorne Deming reads Sharon Allen's essay "Lost in Translation" Tucson City Councilmembers Nina Trasoff (left) and Regina Romero

Tucson City Councilmembers Nina Trasoff (left) and Regina Romero U.S. Congressmember Raúl Grijalva makes opening remarks

U.S. Congressmember Raúl Grijalva makes opening remarksSaturday, November 22, 2008

Adapt and Overcome

Sharon Allen is the author of the Powder essays "New Definition of Dirt," "Iraqi Entomology," "Lost in Translation" and "Combat Musician." Her writing has appeared in Operation Homecoming: Iraq, Afghanistan and the Home Front, in the Words of U.S. Troops and their Families. The following is excerpted from her nonfiction manuscript, 100 Things I Learned in Iraq.

Sharon Allen is the author of the Powder essays "New Definition of Dirt," "Iraqi Entomology," "Lost in Translation" and "Combat Musician." Her writing has appeared in Operation Homecoming: Iraq, Afghanistan and the Home Front, in the Words of U.S. Troops and their Families. The following is excerpted from her nonfiction manuscript, 100 Things I Learned in Iraq.The National Guard was a big shock to me. I just signed and shipped to Basic, having never been to a drill weekend. I knew nothing about the military. Didn’t even know how to stand at attention when I was sworn in.

I was the first one in my class to get into trouble, too. By smiling. I always got into trouble for smiling. I couldn’t help it, drill sergeants say some funny shit. When they got on the bus, it was like I was transported ringside for a WWF match. "Welcome to my world; welcome to Hell!"

The worst part of basic was the mental shit they’d do to you. Whenever one particular fuck-up fucked up, I was designated to be smoked for him. "Smoking" someone is when a drill sergeant comes up with a plethora of incredibly painful things for a soldier to do. A lot of them look easy, too. Try hugging a tree. Go ahead, try it. You have to wrap your arms and legs around the tree and keep from touching the ground. The angrier they were, the bigger the tree.

One time the drill sergeant found a letter I wrote my mom in which I referred to him by his last name, which we were not allowed to do. I also mentioned he was PMSing. At the next formation, he handed me an M60. Then he said, "Over your head." No problem. "Lap formation." Slight problem.

An M60’s pretty damn heavy. Especially over your head, lapping formation. I couldn’t actually run with it over my head, anyway. I’d put it on my shoulders and run, and then put it over my head and walk. Knowing that I hadn’t really done anything wrong (while other people had, and hadn’t been given anything to carry over their heads) and knowing that there really wasn’t much more they could do to me, I started pressing the M60. And smiling as I sung cadence at the top of my lungs.

So, the M60 was assigned as a personal battle-buddy. I had to sleep with it, shower with it, bring it everywhere. I named it "Sam" and cuddled up with it every night. Caused some bruises, but that’s OK.

They took it away from me four days later. They later told me I was getting too much respect from the other soldiers.

I wasn’t a total smartass. The only reason I got away with anything was that I busted my ass, and I always completed everything. I wasn’t a fuck-up, and they didn’t try to "break" me. They just pushed me to be my best. To this day, I don’t have to worry if my car breaks down seven miles from an exit. I know I can road march 15 miles, and with full battle rattle.

I learned a lot in basic training. The most important thing you learn is that you can do a hell of a lot more than you think you can.

And, of course, to "adapt and overcome." We had a handbook that was a part of our uniform, (an "inspectable item"), called a "smart book." Had to have it with us at all times. One time the DS told us to pull out our smart books and noticed that mine was a little thin.

"Private Allen, where are chapters one through four?”

"Drill Sergeant, I have chapters one through four memorized verbatim."

"Private Allen, where are chapters one through four?"

"Drill Sergeant, there was no toilet paper in the latrines."

"Private Allen, where are chapters one through four?"

"Drill Sergeant, I wiped my ass with chapters one through four."

Adapt and overcome.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Powder in Chicago

Powder Authors read on Veteran's Day 2008 at Women & Children First in Chicago. From left to right: Elaine Little Tuman ("Edit and Spin"), Sharon Allen ("Lost in Translation," "Iraqi Entomology" and others), and Dhana-Marie Branton ("American Music").

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Powder at Arlington

Above: Powder contributors (left to right) Cameron Beattie ("Leaping to Earth"), Judy Boyd ("The Joust") and Terry Hurley ("The Dead Iraqi Album") at the Women's Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery on Veteran's Day 2008

Sunday, November 9, 2008

Bringing Home Phryne

Deborah Fries is the author of the Powder prose poems "Alabama" and "Hartsfield-Atlanta Baggage Claim." She joined the US Air Force in 1968, during the Vietnam War. Fries is the winner of the 2004 Kore Press First Book Award in Poetry and is the former Poet Laureate of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

Deborah Fries is the author of the Powder prose poems "Alabama" and "Hartsfield-Atlanta Baggage Claim." She joined the US Air Force in 1968, during the Vietnam War. Fries is the winner of the 2004 Kore Press First Book Award in Poetry and is the former Poet Laureate of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.He came back to the States in a body cast, encapsulated, bearing a bronze star, a purple heart, and a present for my mother: a 14-lb, signed, bronze nude, cast in Europe – probably Poland – circa 1890. He also brought hip and back pain and night terrors that would be his for life. Medical records from an era that did not recognize PTSD document that he lived with an inordinate fear of death, beginning in his early 30s.

He never talked about what he did in the war, or the day that his driver drove them over a land mine or his feelings about what happened to the driver. In his last decade, he framed the photo of the jeep’s remains and kept it on his desk, as if to remind himself that once it had been possible to cheat death, and that it might be again. He died in 1997 in a V.A. hospital, where he spent the last 18 months of his life unable to remember the war or his post-war occupation or home.

The bronze statue came with a narrative that I had learned by five. I heard how my father pilfered her from a German manor house the winter he was wounded. How, cold and tired and long deprived of all civil comforts, his squad occupied and indulged themselves in that grand house in the Black Forest: how they ate caviar, drank champagne, poached good art. It was the only war story he ever told.

The word PHYRNE is chiseled into her base. A little over 17 inches high from her marble plinth to the top of her classical head, she appears in even the earliest photos of my childhood. On a bookcase, end table, eventually on her own pedestal. In some Christmas photos, she is surrounded by holly or angel hair. I was an adult before I learned that the lovely Phyrne had been a famous 4th century BC Greek courtesan, known for her beauty and willingness to adjust her prices for customers who appealed to her.

For more than 50 years, she remained the tangible and mysterious souvenir of war in our home. The Nazi flag, mortar shell casings, chunks of a demolished German pill box eventually were stowed out of sight, but Phyrne remained gracefully on naked display. Like huge periods of my father’s life that were never discussed, she was the small goddess of a house where no one talked about unpleasant things, where decorated fathers bring presents home from war. She was a siren whose call I could hear. And when I enlisted, I sensed that I would enter my father’s world, bring back something valuable, that I would know things men know.

The military was not the place to work out Oedipal issues. Two decades after my father returned from Europe, I trained for another war, then fled from its possible horrors, impulsively marrying a man who had just returned from Southeast Asia. But with no medals, no cached beauty.

I traded a war-wounded father for a war-wounded husband who – like my father – never reported from the emotional landscape he’d traversed. All his stories from Viet Nam were carved out of a dark humor, in which stoned medics queued up to visit prostitutes or stood along the flight line, taunting the pilots as they took off. I traded being a corpsman pushing bed pans in Alabama for being a wife in Wisconsin, and both tours seemed to be about tending to the unknowable.

So, unlike my Powder sisters who actually went to war and know its reality, I am most familiar with the ghostly artifacts of war – the disassociated wounded who I knew only after they’d returned. Instead of a valuable bronze, I brought back an awareness that even if you spend all of your energy trying to comfort or fix someone, you may never be certain about when he or she was broken, or to what degree. You may never have the psychological hotwash or the spiritual after-action review that can explain who you loved or why your love was not enough.

I honor the women who went to war and came back able and willing to tell their stories; they are braver than I was, braver than men I loved, lovelier in their courage to be real than any idealized version of a woman, having brought back in their voices something living, mortal, transient, present and strong.

Saturday, November 8, 2008

Powder Writer Responds to Book Trailer: Let's Not Perpetuate Stereotypes of Military Women...and Men

Charlotte Brock is the author of the Powder essay "Hymn." Her interview with Liane Hanson of Weekend Edition Sunday can be heard here.

I think the book trailer is great and you did a wonderful job putting it together. I do have one comment though.

To say that women see or experience war differently than men is a questionable statement. I think that women see and experience war the same way as men 90% of the time. They have the same reasons for joining, the same experiences, the same worries, anxieties, joys, successes... They just also have a few extra experiences or views that most men don't. But for the most part, women are just soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines... no better, no worse, and not that different. To say that we are intrinsically different just because of our gender actually could be a disservice to women who are trying so hard NOT to be singled out. It implies that we are more sensitive, therefore more in need of extra consideration and special treatment...

You can see how this is a slippery slope. The thing to keep in mind is that we authors do not represent "women in the military." The very fact that we are writers makes us exceptions to the majority of military women. Because we write, we are sensitive beings, we do think about things more deeply than most people, male or female. There are many, many sensitive military males out there, who experience things differently than the majority of military people. To say that we have a different experience than men who feel compelled to perpetuate a masculine posturing is really falling back on and reinforcing a stereotype of military men that can be harmful both to gender relations within the military and to perceptions of the military by the general public.

And why would the fact that women are not easily accepted in the military make women see things more objectively than men? We may... but this argument needs some backing up. As I said, the women who wrote for this book are exceptional among military women because they are writers, and because they chose to share their experiences for this book. Many, many (I would say most) military women are just as bit as swaggery, "insensitive," straight-shooting, etc, as some of their male counterparts (and are these characteristics really "male" or are we just told that that's what being masculine means?). Many have absolutely no experience of sexism in the military. Some really resent the women who point out the differences between men and women, thereby making it more of an issue, and more difficult for them to fit in seamlessly.

I am not saying I am one of them... But men who oppose women's full participation on the battlefield will use exactly the same kind of argument: women are different, women need to be treated with sensitivity, women deserve special consideration, women represent a more delicate, complex type of person than men. Therefore they should be protected, therefore they do not belong on the battlefield.

Yesterday, at Col John Ripley's funeral, the Commandant of the Marine Corps spoke. And for some reason, he felt the need to mention that Col Ripley, although supportive women's presence in the military, was adamantly opposed to women being in combat zones or filling combat roles. He said (and this was at the Naval Academy, in front of an audience of male and female midshipmen), that women are different from men, that they should never be in combat, and that there's sheep and there's wolves, and on the battlefield, the sheep are always going to kill the wolves.

Needless to say I was shocked and saddened and demoralized, as I sat there in my uniform, with four medals awarded in part for being in a combat zone, knowing that all those young female midshipmen who were trying so hard to earn their place were probably sitting there sad and confused... He had just made it so easy for the male midshipmen to look down on the females, to view them as second-class citizens, not quite their equals. (Comparing us to sheep was just really uncalled for). And that's coming from the senior person in the entire Marine Corps, someone who's supposed to at least pretend to be supportive of his thousands of female Marines, many of who are busting their butts to accomplish the mission he sets for the Marine Corps in combat zones today.

Col Ripley held the view that women represent the best, most precious aspect of what it is that men fight for, or the homeland, and that because of this they don't belong on the battlefield. When we women emphasize that we are different, that we have a different perspective, it reinforces what people like the commandant think: that we are a different species from men and that we need protection, not equality (and equal opportunity to compete for all jobs and positions.)

I don't know what the other authors think, but I would suggest that we all try to refrain from making generalizations about men or women in the military. There may be some very open-minded, pro-women military guys out there who really want to like this book but are a bit turned off by the suggestion that military men are mostly swaggering macho types and that women, by virtue of being women, have a deeper understanding or perspective than they do. Many war stories written by men show deep sensitivity and complex emotions and insights, and little swaggering. (A Soldier of the Great War, Goodbye Darkness...)

I just wanted to say this to add to the discourse and maybe bring up some issues that may not have come up yet. I love the book and the essays and think it's important to get a feminine perspective out there. But we all speak only for ourselves, and our experiences have at least as much to do with our individual personalities and circumstances as our gender.

--Charlotte Brock

Friday, November 7, 2008

Sexist Guy Digs the Book

Shannon Cain is the co-editor of Powder

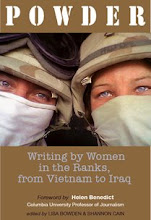

Jack Lewis at crosscut.com is eager to inform us early in his book review that combat is "the world's real oldest profession" and that "cover girl" Sharon Allen (pictured on the book with her buddy Kim Archer behind the wheel of a D7 dozer) is a “big, loud sexy Sergeant.” Gee, Sharon, congratulations.Lewis advises readers to skip the “doctrinaire shrillness” and go straight to the guts of the book: "Powder is blemished by the cant of its creators, their nakedly political agenda bleeding through every syllable of the preface."

Yet Lewis waxes wildly enthusiastic ("lucid narratives and whisky-strong poetic imagery") about the essays and poems in the book, which only goes to show you that even a couple of peacenik feminists can manage, after all, to hang onto their editorial integrity.

Veteran's Day Book Launch Events

Terry Hurley, Cameron Beattie, Anna Osinska Krawczuk, and Judith K. Boyd

Women's Memorial Veteran's Day Ceremonies

Arlington National Cemetery, Washington DC

3:00 p.m.

Sharon D. Allen, Elaine Little Tuman, and Dhana-Marie Branton

Women & Children First Bookstore

Address, Chicago, IL

7:30 p.m.

Charlotte Brock, Christie Clothier and Elizabeth Keough McDonald

Downtown Tucson Main Library Plaza

101 N. Stone Avenue, Tucson

12:00 p.m.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)